|

A long time ago (sometime in the 1980s), I gave a paper at a regional Costume Society of America meeting. I can't remember the topic, and it isn't even listed on my CV. Only one thing stands out in my memory: I was introduced by Richard Martin, at that time one of the brightest stars in the fashion studies firmament. Only one year my senior, Richard was an established curator and scholar, producing several blockbuster exhibits a year at the Fashion Institute of Technology. He had graduated from college the same year I graduated from high school, and earned two master's degrees while I was still waiting tables. In short, he was brilliant. He was also gracious and generous; there are many "stars" in academic fields who are willing to lower themselves to occasional brief appearances at conferences, where they hang out with the other stars and ignore everyone else. Richard was not that person. So it was that Richard Martin (THE Richard Martin) was at a regional meeting presiding over a session of papers by junior scholars and graduate students. I was probably the most senior presenter, but still an assistant professor; my very first article about boys' clothing and gender had just been published in Dress. And he introduced me not just with a list of my degrees and positions, but a description of my work. WHICH HE CLEARLY HAD READ. And he called me an iconoclast. On my secret, imaginary business cards ever since, is the line "Richard Martin called me an iconoclast". Yesterday I got this message via Linkedin from Rob Smith, founder of The Phluid Project, a gender-free store in New York. Greetings! So: iconoclast icon? Iconic iconoclast? I think what it means is "don't stop". So I won't!

0 Comments

I have been writing less these days because mostly I am doing research, either for my next book or for a series of church history articles for my congregation's newsletter. So poor "Everything Else" has been sadly neglected. This little lagniappe will have to do for now. On page 224 of The New Seventeen Book of Etiquette and Young Living (1970), in the chapter about manners on the working world, author Enid Haupt lists a range of exciting career opportunities now open to women, especially in science and engineering. She offers this anecdote: A young career girl barely out of college, with a brilliant bent for math, helps bring astronauts back from the moon through computer calculations at a space center. I doubt that Haupt was making up that story; as Seventeen's publisher and the author of a regular column in the magazine, she must have known about the "computers" at NASA - women hired to do the extensive complex calculations that made space exploration possible. As we know from the Hollywood film "Hidden Figures", many of these women were African American. In fact, the "computer" who performed the trajectory calculations that assisted the 1969 moon landing was Katherine Johnson, played by Taraji P. Henson in the film. Knowing this, I could not help but wonder why Haupt had "hidden" her race? Why depict her in the anecdote simply as "a young career girl"? Haupt does not completely ignore race in her 321-page book. Chapter 5, "Pride and Prejudice", devotes its entire three pages to racial and religious discrimination, and it is a reminder of the cultural environment that shaped today's older adults, especially the white women who were Seventeen's predominant readers. Her points:

Perhaps like Katherine Johnson became an outstanding mathematician, only to be rendered invisible 200 pages later. I can't imagine that many of Haupt's white readers in 1970 would argue with her advice. Speaking for myself, in the first part of the chapter, she pretty much describes how I was "taught" to deal with difference. Prejudice was a personal flaw to be addressed in the same way as poor posture, through individual effort. The Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act had eliminated the "big issues", and all that remained was a bit of attitude adjustment. People just needed to be more open-minded, and some people needed to get that chip off their shoulder. By now we should know better.

ETA: The phrase "politics of respectability" seems appropriate to what I am finding in etiquette books. Can you imagine how the world would be different today if the people who have been climbed over, stepped on, and silenced had been able to tell their own stories, play their own music, create their own art? Can you imagine how the world could be different without fame and success being the reward for oppression, cultural theft, and abuse? I wonder about this all the time, more and more thanks to #BlackLivesMatter #MeToo and #TimesUp. Was "Annie Hall" brilliant because of Woody Allen's appalling sexual behavior, or in spite of if? Does the beauty of the blues justify 400 years of slavery and Jim Crow?

It's one thing to know that terrible circumstances can result in amazing works of expression. It's another to believe they are necessary, and accept crimes against humanity as the price to be paid for those works. And it is still another to admire or even protect people who use other people as objects or chattel because we like their music/art/athletic ability/writing/politics/comedy. That's where I am this morning. I had an interesting conversation with a visiting journalist from India not long ago, in which she asked about how I had organized my research career. The short answer is that it was not exactly organized; in retrospect, it seems more orderly than it was. Here is how I see it now: What was particularly helpful for me personally was realizing about forty years ago, as I was starting my PhD, that my goal was not to understand fashion, but to use fashion as a lens to understand gender. That freed me to use other lenses as well, while building my specialized expertise in fashion. So while my research and writing focused on clothing, I read far beyond clothing, and read less of the fashion literature that did not incorporate gender. What I have learned about toys, food, film, and other cultural products that also reveal gender has helped me understand fashion/gender better. Within the last twenty years or so, I have expanded this frame of reference to reflect my realization that gender is itself a lens through which I study culture. I wonder how my work would have been different if I started out forty years ago focusing on culture, then narrowing to gender and then to fashion. But evidently that is not how my brain works.

I cannot tell a lie. No, really. The best I can do is just keep my mouth shut and hope that people interpret my silence as agreement. That's probably why writing history comes easily for me, with its comforting foundation of dates, quotations, and artifacts. Whatever interpretation one wants to draw from the evidence, the evidence is there for anyone to handle and inspect. Boys used to wear dresses. There was no "girl color", pink or otherwise. Make of it what you will, but the facts won't go away. After he was forced to recant his claim that the earth orbits the sun, Galileo allegedly muttered "And yet it moves", because there really are such things as facts.  Yet all my life I have longed to write fiction and poetry. I usually explain my inability to make up stories in terms of my innate honesty; I cannot tell a lie, therefore I must write nonfiction. But over the last few years, a strange transformation has occurred in my brain. Whether I am in conversation, watching the news, or just planning my day, I become aware of a second, ghostlike consciousness telling the same story, but with a twist. The most vivid version of this has been in meetings, where "surface Jo" is listening politely or offering her measured opinion, but "alternate Jo" chimes in. Her voice getting louder and louder, she makes rude comments or imagines more and more fanciful variations of what is actually going on. I used to worry that her words would suddenly appear running across my forehead for all to see, like a movie marquee, until the day a few weeks ago when I said them right out loud. I clapped both hands over my mouth, but it was too late. I take this as a sign. Either I am showing early signs of some kind of cognitive decline -- impulsive behaviors are associated with Parkinson's Disease, or various forms of dementia -- or my inner storyteller is trying to be heard. It could be both, but either way, it feels like it is time to pay attention to alt-Jo and transcribe those stories. Here's the curious thing: I still cannot tell a lie. My stories will be true, although they may not be factual.

My plan was to savor this last semester, but of course life got in the way, as it always does. First there was pneumonia, then catching up from pneumonia, then spring break, then catching up from spring break, then the Popular Culture Association conference, then catching up. Now it's the last week of classes, and I am determined to be attentive each day.

On Mondays I usually work at home, but today we had a faculty meeting, so I did some correspondence and editing in the morning, then hopped on the UM shuttle, arriving a bit after the meeting had started. Such is the bus commuter life. I also did a quick draft of today's story, which I will post anon. My very first faculty meeting was January, 1975, at the University of Rhode Island. I was a lowly master's student, and graduate students usually did not attend faculty meetings. But because I had full responsibility for a course, instead of assisting with one, they decided I should come to the meetings. The initial experience was not unlike running into your teacher in the locker room at the local gym for the first time. All their authority was stripped away, as they called each other by their first names and chatted about their families and their weekends. I can't remember saying anything in the first meeting, or ever, in the three semesters I taught at URI. but I enjoyed the meetings, or at least can't remember disliking them. The faculty meetings in the Textiles and Consumer Economics department at the University of Maryland, in contrast, were brutal. In the first place, they were on Friday afternoons, and they lasted two or three hours. The only good thing was that we repaired afterwards as a body to Happy Hour in the old tavern across the street. But our meetings were usually substantive and often contentious, so Happy Hour was necessary. I believe we met every other week, the day paychecks came out. So if you wanted your paycheck that day, you had to show up. (I pause for a prayer of gratitude for direct deposit.) Since 1993, I have been in the American Studies department, a kinder, gentler culture when it comes to meetings. They have been few and far between, nearly always genial, and the advent of wifi has made it possible to multitask during discussions. Today was my last faculty meeting, or as I like to think if it, my LAST. FACULTY. MEETING. EVER. I like my department, and I like my colleagues. They are a smart, friendly bunch. I look forward to future meetings, but meetings with no agendas except good conversation. Getting dressed has been an easy routine for years. I pick my shoes first, based on the weather and how much walking is involved in my day. If I am working at home, it's bare feet or slippers. Then I pick my jeans or capris (again, it depends on the weather and if it's a campus day or a home day). A solid color T-shirt. Sometimes the shirt is sleeveless, and the neckline varies. If I am going away from home, I might add a scarf. I always wear earrings. I rarely wear a skirt or dress once the temperature falls below 60 degrees, and I never wear jeans once the mercury is above 80.

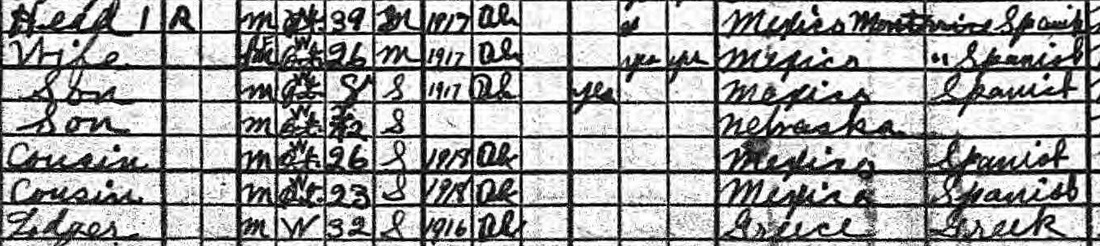

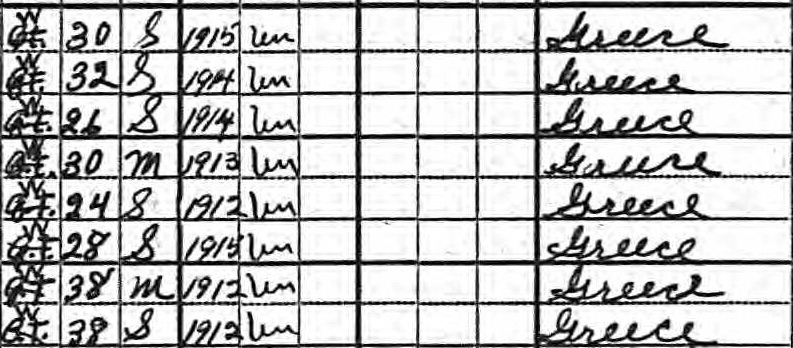

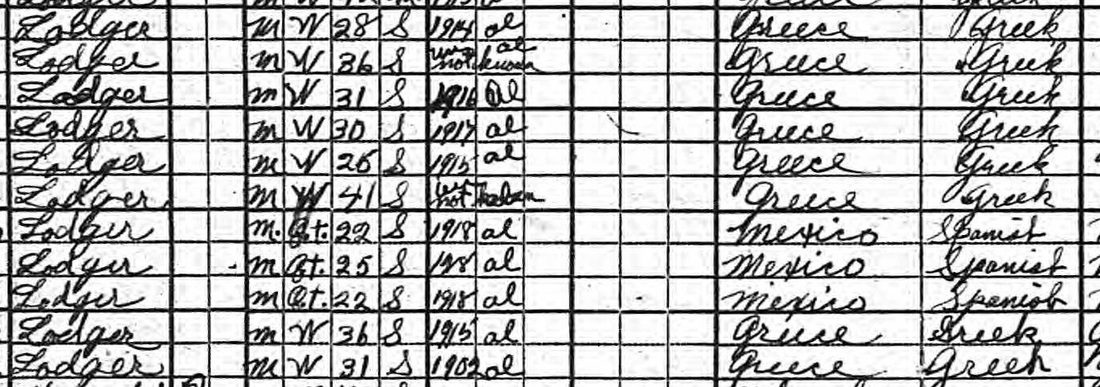

I will admit to not being much of a fashionista. I would rather spend my time and energy (and money, which I earn with my time and energy) on a few things I can wear 90% of the time than on many items I seldom wear. The 10% items in my wardrobe are special, and I enjoy the rare occasions when I pull them out. When I travel, I pack light. For a week at my favorite retreat, Star Island, I take a pair of capris, a multicolored skirt, seven T-shirts, and a sweater for chilly mornings and evening. Here's my wardrobe, which doubles as a calendar as I move through the week. I got there on a Saturday. Can you tell what day I took this photo? My parents had a mixed marriage; Mom was a Republican, Dad was a Democrat. Now mind you, in the 1950s, that didn't mean much. The first President I remember was Eisenhower, and he would be considered a RINO by today's GOP base. My mom's family was decidedly Republican, as were many German Lutherans in the Midwest. My mom had little use for Catholics and Jews, but of course that was expressed in the nicest midwestern way ("not our kind", and a tendency to point out which Hollywood stars were Jewish, even when the information was a complete non sequitur). When she moved to Maryland in the 1980s, she had several Black friends; I know, because she never failed to identify them as "my Black friend so-and-so." My dad, raised below the Mason-Dixon line in southern New Jersey, had grown up in a small town that sanctioned interracial friendships but not interracial dating or marriage. He idolized Satchel Paige, Louis Armstrong, and Lionel Hampton, but he also laughed at Amos and Andy and told racist jokes. I have seen a picture of him in blackface for a minstrel show in Port Norris. But his dad trained young Black men as typesetters and printers and sold his print shop to one of them when he retired, to the disapproval of his wife and many of his neighbors. So, like many white Americans, my personal history with race and racism is complicated. So is the racial history of North Platte. I am a huge fan of Ta-Nehisi Coates, and his take on the social construction of race. In Between the World and Me, he uses the phrase "people who call themselves white", which underscores the historical fact that many groups who are now considered white were once not considered part of that privileged and protected group. (And, I might point out, the legal and social history of those privileges and protections, from personhood to public accommodation, to voting rights.) This is how complicated it was in 1920. The local census enumerator, Mary Durbin, had a bit of trouble assigning racial categories to two particular groups: Mexicans and Greeks. Compare these entries: Over the forty or so pages of Mrs. Durban's enumeration, the Greeks became White and the Mexicans became Other. That is how slippery a thing this thing called "race" is. And what about me, in 2016? I call myself White; my ancestors came from Germany, England, Ireland, Scotland, and -- surprisingly -- Sweden and Italy. I, too laughed at Amos and Andy and listened to Louis Armstrong. I danced to the Temptations, and read Uncle Remus stories. I sang "My Old Kentucky Home" and "Old Black Joe" in school choir. I also voted for Barack Obama (twice) and follow Charles Blow, Joy Reid, and Van Jones on Facebook and Twitter. I think reparations need to be part of any discussion about racial reconciliation. We need to be as familiar with our nation's white supremacist past as with the civil rights movements that have struggled against it. We need to know white supremacy when we see it, whether in everyday interactions or national news. Would my views of race and racism would be the same if I had lived my whole life in North Platte? I would like to believe the answer would be "yes", but in my heart of hearts I know that is unlikely. The harder question to answer is how much of the racism I learned long ago still lingers in me.

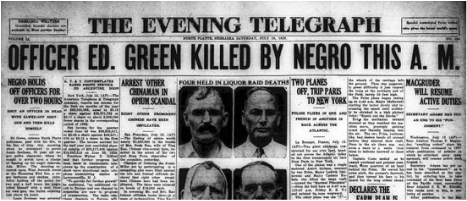

My wanderings here in North Platte have taken me back to the microfilm machine at the library, and the 1929 North Platte Evening Telegraph. Long ago, I had stumbled across a news article in the New York Times about a "race riot" in North Platte. I was researching something else, and this was when photocopy machines were uncommon, even at the Library of Congress, so I didn't save the story, or even take notes. But I remembered. And as the Internet expanded, I would try to find more information from time to time. Here is what you'll find today about the incident. On Saturday morning July 13, 1929, in North Platte, a white police officer was shot and killed by a Negro he was trying to arrest. The slain officer was Edward Green, a well-known former acting chief of police, and one-time professional baseball player. The black man was Louis (Slim) Seeman, operator of the Humming Bird Inn, a chicken-dinner lunchroom located in his home on West 7th Street. Shortly afterward Seeman, too, was dead, either by his own hand or as result of police gunfire. Following the shooting deaths, a small group of whites threatened the city's black citizens, most of whom had fled by late afternoon. If you read the whole article, you see that it's a very complicated story. The news reports were eventually found to have exaggerated, adding lurid detail, increasing the Black population of North Platte from around 30 to 200, and describing nonexistent babies nearly drowning as they escaped in a rain storm that never happened. But there are also bits of truth. There was a small group of men who circulated among the Black community and warned the residents to get out of town by 3 pm. There was a Ku Klux Klan presence in the town at the time. The men accused of chasing the Black people away were tried, and all were acquitted. The entire incident is still blamed on the Black people; an acquaintance told me last week he had heard about the story, but that "there was a lot of prostitution and crime in that neighborhood". The claim that Seeman shot the officer and himself with the same sawed-off shotgun is contradicted by the autopsy. So what matters? Is it a happy ending that it wasn't a race riot, after all?

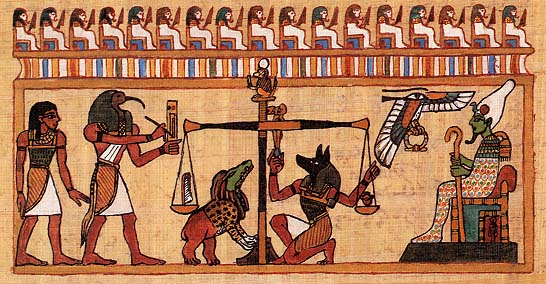

So now that I have recapped my experiences visiting my home church in North Platte, let's go deeper and answer the question, "Would I still be a Lutheran if I had not moved away". It's quite possible I would still belong to First Evangelical Lutheran Church. After all, I am the person who posts the same thing at the beginning of Lent every year: I want to give up inertia for Lent, but I can't get started. I joined the Unitarian Universalist Church of Silver Spring in the fall of 1982, and am still a member, despite ministerial crises and all the usual nonsense that goes on in any organized religious community. But it's still my community, and the longer I stay the harder is it to leave, because my social life is firmly rooted there. I can't even contemplate retiring elsewhere because it would mean leaving nearly all of my friends, and I have already done that enough times for one lifetime. So if I still lived in North Platte, I might be one of the gray-haired ladies who are holding the congregation together, even as two more Lutheran churches opened in town. And even though the Episcopalians and the Presbyterians are (reportedly) more liberal. But I would probably not be theologically Lutheran, and here's why: See the little angel on the right, looking up at the tin-foil covered toilet plunger? That's four-year-old-me. There are three photos of this Christmas pageant from 1953, and in every single one I am peering at something, instead of being a good little angel. In one, I am giving the photographer the side eye. In the other, I am peeking into the manger, looking at the flashlight playing the part of Baby Jesus. That was me -- like the Elephant's Child, insatiably curious. Once I learned the hard truth about Santa Claus, I also became incorrigiably skeptical. We had family "devotions" every night as long as we lived in North Platte, complete with a reading from scripture and a story from our Bible storybook. But I also read Grimm's Fairy Tales, Edith Hamilton's Mythology, Mary Poppins, and lots of Dr. Seuss. When I moved to New Jersey, two things happened that set me on the path to Unitarian Universalism, even though it would be another 35 years before I walked into a UU church. The first was a sixth grade unit on ancient Egypt. The teacher was describing the Egyptian belief that after death their souls (located in their preserved heart) would be weighed/judged by the gods. The rest of the class laughed. I thought, "What if they were right?" The second thing happened my first year of confirmation class at Zion Lutheran Church, in Westwood, New Jersey. The Eichmann trial was in the news, and it was the first time I had ever heard of the Holocaust. Don't be shocked; I am half German on my mother's side and we did Not Mention the War. But images of the Holocaust were in Life magazine, which arrived in our house every week. I had Jewish classmates and friends, including my Girl Scout leader and most of the girls in our troop. The lesson in confirmation class that week was the core Lutheran doctrine of justification by faith. As the sweet, elderly German pastor explained, that meant that the only path to salvation was belief in Jesus as the Messiah. Everyone else was going to Hell. "Even the Jewish babies?" I asked, thinking of the horrific photos in Life. And Pastor Jacob shrugged and said "I'm sorry". At that moment I became a Universalist. So, assuming I would have encountered the same challenges to my faith in North Platte (except for the Jewish friends part), where would that lead me? in my alternative history of myself, I would take my skeptical, curious self to the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, and one of two things would happen. The first possibility is that I would discover Unitarian Universalism and find a home, as I finally did in 1982. The second is that I would go to my father's alma mater in my birthplace in Fremont, Nebraska, major in religion and follow in Elizabeth Platz's footsteps and become a Lutheran minister. After all, I do come from a line of pastors. Maybe the Reformation was not the end of Revelation.

|

Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed